In 2009, the Morgan Motor Company, based in Malvern, UK, is celebrating its centenary year. With a series of events scheduled to mark the occasion, there is perhaps none more important than the April opening of the company’s new visitor centre. During the summer, the facility is expected to welcome up to 600 people each week, interested in learning more about the company and its cars.

According to Steve Morris, Operations Director, visitors hold the same passion for the cars as do the buyers that continue to fill Morgan’s order books and underwrite its success. In fact, he is acutely aware that without this support, the company could well be one of the companies posting dramatically reduced sales figures.

“When you look at some of the high-end manufacturers that are suffering, Jaguar, Aston Martin, Land Rover, I can imagine it’s tough. We had a meeting before Christmas where we acknowledged we’re in a fortunate position; we should keep in mind that there are a lot of less fortunate people involved in the (carmaking) business. At the end of the day, it’s people’s jobs and incomes that are at risk.”

Give the people what they want

To succeed in a shrinking market, it is said that carmakers need to meet two criteria; they must make new, innovative products and those products must appeal to potential buyers. While Morgan is famous for producing roadsters that evoke memories of motoring days past, on-going improvements in build quality have created products that successfully fulfil both requirements.

Key to this is the way in which the current model range is produced. Both the classic (Roadster, +4 and 4/4) and Aero (Aero8 and AeroMax) models still feature wooden, coachbuilt bodywork, so-called as it uses skills carried over from traditional carriage making. Advances in material preparation have, according to Morris, raised this craft into what he terms ‘wood engineering’.

“The cars all have coachbuilt bodies, but on the Aero and AeroMax, we’ve gone down a different route with using wood to where it’s more than coach building. We’ve still got all the same techniques and skills, but now there’s engineering and science behind the wood, especially in the parts where we create complex shapes from solid and laminated wood.”

In as much as wood can be considered a ‘traditional’ material, the production process behind the more complex aluminium body parts is straight out of the modern era. Using a technique known as super plasticform (SPF), Superform Aluminium, based in Worcester, UK, creates much of the bodywork for the both the classic and Aero models.

“Back in the late 80s and early 90s, SPF was very much an aerospace technology,” says Morris. “Superform (Aluminium) produces the front and rear wings and a high percentage of body panels for the classic models. For the AeroMax, they produce the whole body. In fact, the AeroMax is the first all-aluminium superformed vehicle in the world.”

To create a superformed part, a sheet of aluminium is heated to 4500C before a bubble is blown through metal and it is laid over the forming tool. Software-regulated air and tool pressure are then used to form the metal to the mould. It’s a technique that allows the creation of extremely complex panel shapes.

Is superforming a tool for convenience, or a tool that allows Morgan to achieve something that otherwise couldn’t be done?

“It’s a tool for repeatability, for quality,” explains Morris.

“Superform isn’t a high-volume process. The typical hold time on a Morgan wing is about 40 minutes, so there would have to be advances made in the technology before it could become more widespread. The manufacturers that use superform now are generally lower-volume manufacturers, Rolls-Royce, Bentley, Aston Martin, Spyker, Lotus, Ford (for the GT) – but it’s an impressively clever process.”

Without the superform technique, Morgan would have likely continued to build all car wings by hand, but as Morris explains, “Customer expectations with regard to build quality and repeatability could never be achieved with the way we used to build the car. The quality wasn’t there, there was too much rework, too much warranty work. The quality of the vehicle has improved dramatically.”

Using wood to build cars is a tradition that Morgan Motors has continued throughout its history. That said, the skills of the artisans building the ash frames for each Morgan are now complemented by a series of modern techniques, which Steve Morris, Operations Director, says has taken the wood craft to new levels of complexity. “Coachbuilding is the historic side of Morgan, the side that people love, but so much technology is applied to the wood that it really qualifies as what we call ‘wood engineering’, particularly in how the wood is married to the metal.”

Like much of the Morgan build process, the fabrication of the wood frames and even the sourcing of the wood is under constant revision. “It’s only ten years ago that we used to buy whole trees,” says Morris. “Now we buy everything in (pre-cut) wood billet form. These are nested together and bandsawed – a very low tech, mill stage.”

While some of the wood undergoes only minor manipulation, other parts are shaped and formed using surprisingly diverse methods. In some cases, laminated ash ply is shaped in traditional G-clamped presses, while similar material is bagged and compressed in a process very much like that used to shape carbon fibre.

“From that point, we take the wood and make the body frames,” says Morris. “Racks are divided by model, Aero 8, AeroMax, etc., and all of those racked parts equal a body. Create the frame and you have the raw ingredient that is every Morgan.”

The magic’s in the mix

The continued success of Morgan is due in no small part to the fact that each car is purchased before it goes into production. Once the sales order is received, the details are loaded into the system and this produces a works order and bill of materials. At the same time, Morris issues what is referred to internally as the ‘build book’, an internal document that is assigned to each vehicle and used to track the full production process.

Exploding out the work order, parts held at the factory are loaded into model-specific parts trolleys, wheeled carriers that are designed and fabricated in-house. Loaded and labelled, these meet the corresponding cars in the final production area, where the on-board parts will be kitted and assembled. All parts are itemized in the build books.

“We kit about 85% of what goes on the car, about 20,000 items per month,” says Morris. “As a process it’s still evolving, we still might find a better way to do it, but the day you stop looking for a better way to do things, those are the dangerous days.”

To some degree, the company is beholden to produce vehicles based on the received orders, but Morris prefers to keep a varied model mix running through production. “As a company, we try to keep the model mix very stable.

We wouldn’t want to build 15 +4 models a week because it doesn’t offer sufficient yield for the business, from a profitability point of view. So we try to keep the model mix as fat as we can. This helps keep stability in production, plus it also helps when planning for buying parts. Because we are not doing tens of thousands of cars, we have longer lead times on certain parts, so (having a good mix) allows us to plan that better.”

An ISO 9001/2000-approved document, the build book offers multi-layered reporting in regards to traceability, quality checks, manufacturing times and a range of other build details. Says Morris, “Every job has a standard time, worked in minutes, which is checked off in the build book.

“We try and keep takt times as similar as we can in every station - that’s something we’re continuing to work on - currently its 135 minutes. It’s one of the issues I’m looking at now, because if you build a four-seater model, that gives you different problems than a two-seater. Even if you put another guy on the job, they can’t work on top of each other. This year we’re planning on adding more Aero products, so that’s something I’m going to have to take into consideration.”

As for inventory, it’s based on stock rather than the anticipated production of each model. “We target a 44-car WIP in the factory, that’s not including finished goods; completed cars are not included. At present we’re running just slightly over, at about 50 cars. Ten years ago we were running at about 120 cars WIP, which was without the Aero.

Looking at it now, I don’t know where we put all those parts.”

Limiting inventory is a widely-accepted method for cutting overheads, but Morris admits there are exceptions, especially for low-cost parts that are easy to store. “Some parts, we have enough for a month of production, others maybe two months and others a year - it depends on a number of factors to do with demand, part price, cost of delivery.”

“We do spares for models that date back to 1950,” says Steve Morris, Operations Director at Morgan Motors. Immediately you imagine a massive warehouse, filled to the roof with parts for every post-war Morgan model. If that’s out of the question, how does Morgan supply such an extensive back catalogue?

“We make the spares on the production line, beside frames for current models,” explains Morris. “We have our own spares department for brought-in components, glass, wiring looms. But for instance, if you have a 1965 Morgan, we can make you a body frame for that car, we’ll panel it, send out a leather kit.”

Like other car manufacturers, spares can prove to be a lucrative addition to the financial bottom line.

“We do about £1.5m on spares a year, over a £20m turnover. The good thing about spares is it’s a profitable part of the business, but it still has to be managed.”

Providing the spares can still be a challenge, owing to the varied ways in which knowledge is stored around the company.

“It’s interesting, because Morgan - the company and the car - has been an evolution. Meaning that you’ve got hard patterns and you’ve got knowledge in people’s heads; providing spares means pulling all that together in a single process. So you can’t just wave a wand and decide to subcontract spare parts production to a third-party company, it wouldn’t work.”

Arriving at Morgan’s Malvern facility, the factory appears deceptively small. Encompassing 90,000 sq ft, the size of the site does not compare with that of larger OEMs, but is sufficient to accommodate what Morris describes as the ‘disjointed’ array of buildings that together comprise the full production area.

“On the outside it doesn’t look that big because of the way it’s divided, but when you walk around, you realize it’s bigger than you think - you can get lost quite easily.”

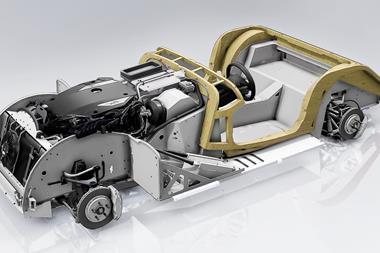

Once a car gets launched into production, the first stage is chassis build. There are two distinct chassis types; the classic models are all based on a carbonized steel ladder frames, while the Aero products feature a bonded aluminium structure fabricated by Radshape Sheetmetal, based in Birmingham, UK. Says Morris of the Aero chassis, “It’s a great chassis, very light, with great torsional rigidity.”

Both classic and Aero products start off in the same area, with individual stations dedicated to one product. Starting with a bare chassis, the engine (including engine dressing), drivetrain, axles (including brakes) and lights are added.

Two- and 1.6-litre Ford engines, supplied by Powertorque, are used for classic models, while BMW supplies its 4.4-litre V8 for the Aero range; an overhead crane assists in lifting the engines. Classic models still require additional work to be up and running, though this is not true of other Morgan models. “If it’s an Aero or AeroMax, chassis build is where the car goes from nothing to a completely driveable chassis,” says Morris. “So you can put the laptop on it, start the car and drive away.

“We always test the cars here before moving them on, the power systems, radiators, because if you get something like a minor fuel leak – even a vapour leak that triggers the engine light - it’s easier to re-configure things like that at this stage.”

To assist in the movement of vehicles between stations, Morris and his team went through a major overhaul of the production line to take advantage of the factory’s hillside location.

“In the last ten years, we’ve completely reconfigured the line, re-laid the factory, as a result of an examination of the assembly process to see how the car was moving. The cars used to go up and down (the hill) following the assembly line, but now the line is mostly gravity-fed. As much as possible, the cars roll downhill wherever they can.”

Having completed chassis build the cars are then rolled (largely assisted by gravity) into the next build phase, body frame, where the wooden frames are fitted to the corresponding chassis. Prior to use, each fully-constructed ash frame is treated in a protim silignum (Cuprasol) wood preservative dip and rack-dried for two days before being sent through to the BIW area. This, says Morris, is enough to stop any rot from forming in the wood. All outer aluminium cladding is then fixed to the wood underbody.

“For the panels that are handmade on-site, we use the coach worked frames as the panel buck,” says Morris.

“Whether they’re handmade or superformed, the exterior aluminium parts are usually pinned, screwed or bonded to the frame. Panels are rarely riveted to the frame, but they can be riveted together.” In terms of labour, this is a one-man operation. “One guy takes a frame and panels that complete frame. There’s a standard time for him to do the job, it’s how we measure and monitor our quality standards.”

The body frame area includes two distinct lines, for both classic and Aero models, each line equipped with air- and battery-powered hand tools supplied by Morelli.

“By two distinct lines, I mean two distinct areas,” continues Morris. “We have a complete department designated for Aero build. In saying that, we are very flexible, so we can switch build numbers in either area to raise production numbers. We also run skills courses, so that the coverage is there when needed. In fact we’ve just upped the AeroMax numbers a little and more than an infrastructure change, it raises personnel issues.”

From body framing, both classic and Aero models move over to the paint area, which features Sata paint equipment (distributed by Morelli) and Junair paint booths. Mounted on dollies, designed and fabricated in-house, the classic cars are primed and painted while still fully assembled; Aero models are fully disassembled before going through the paint process.

“Paint is all applied by hand,” says Morris. “We have fully enclosed booths with heat and extract systems. For curing, we bake off at 600C panel temperature for 30 minutes.

The thing with paint today is that its a very technical area; we have process charts, we probe the panels to check for temperature, we do hardness tests once every 20 cars, we do solvent tests, adhesion tests. We run more paint tests than the large OEMs.”

Morris adds that Morgan must comply with government EPA regulations, including filter maintenance and spray booth checks, including VOC reporting for the paint chemicals. Additionally, the company has to register all waste licenses.

Morgan has exclusively used BASF’s Glasurit paint on all its products since 2006. “As a paint provider, Glasurit has been really good,” says Morris. Morgan uses the standard paint product, but aside from the 4/4 Sports (introduced in mid-’08, with a range of six colour options), customers can choose any colour. These are mixed on-site by Morgan’s own paint specialists, or Glasurit’s technical support department can supply custom paint colour formulations.

Following paint and polish, classic models enter their own dedicated finishing area, including leather, hood (or roof, for standard convertible models – a hard top is an optional extra), interior trim and the famous Morgan wire wheels, now made in India by Motor Wheels Services (MWS).

Painted in separate spray booths, Aero models are then reassembled, doors are kitted and mounted, while seats and remaining interior work is completed.

“Total build time for a classic car is about 12 days, an Aero is about 18 days,” says Morris. “That’s from the start to the end of the plant, not one man for 18 days. An optimum time would be about 11 and 16 days, but we get as close as we can to those numbers while taking into consideration any lag on the line.”

Despite the current market downturn, the order books at Morgan Motors are full for 2009. Were it not for the collective belt-tightening of banks and the buying public, Morris estimates that the company could be building and selling considerably more cars.

“Although we’re not looking to do anything dramatic, like trebling production, I think 1,000 cars a year is a realistic target,” says Morris. “I think our centenary year has generated a lot of interest and we’re benefiting from that. If the downturn hadn’t happened, we’d be having problems meeting demand. In all honesty, we won’t be able to satisfy demand now, but we would have been a lot further away.”

Morgan customers are located all over the world, which in itself adds additional complexity to the build process.

According to Morris, just a year ago there were 12 different dashboard variations (left-, right-hand drive, mph or km/h, etc.). Now there are about 32.

“The classic cars don’t currently conform to US regulations,” observes Morris, “only because of the airbags.

We had a supply of mechanically-operated airbags, but unfortunately that has run out. Since then, we’ve taken the approach that the Aero is the product for America. In saying that, we have whole vehicle approval for Europe, so yes, we look at the market, our R&D department has people dealing with homologation, and we homologate for whatever market is required.

Morris goes on to point out that Morgan conforms to every legislative requirement in regards to safety. He points out that cars have been through the same US 5mph rear impact test as other, much larger OEM manufacturers, the cost of which is disproportionately large for a company of Morgan’s size.

“I think that when you go back to the 1980s, the company embarked on a push for safety, that stood us in good stead. I think we also have to say that Morgan is here today, an independent company, because we have done that. But I still think that if you just looked at the money, you would start to question whether we we’re getting good value. But we’re here today and we’re busy.”