Your webinar questions answered: How tier 1 suppliers are responding to tough headwinds

You asked, we answer. We return to the questions from our audience that we didn’t have time to answer in our live webinar, ranging from which parts of automotive tier 1 suppliers’ business models are at risk of commodification, to how tier suppliers are changing manufacturing processes

In our first webinar, ’How to mitigate falling profits in the automotive supply base,’ we presented findings and insights from our research report into the finances and business models of major global tier 1 suppliers (download the full report here). In a Q&A session after the presentation, we attempted to answer audience questions that ranged from how tier suppliers are changing sourcing patterns, to what the impact of electrification and autonomy will have on OEM and tier supplier relationships (you can view the webinar in full again here).

We didn’t get a chance to cover all of the questions posed during the webinar, and so here you will find our answers to those we couldn’t get to during the live session. Get in touch if you want to discuss these or other points further.

Which are being hit hardest by the challenges and headwinds that you discussed, OEMs or tier suppliers?

Daniel Harrison: Although OEMs are also seeing declining profits, we do think that, overall, more of the burden is and will fall to the supply base. The headwinds around emissions regulations are forcing tier suppliers to help develop more fuel-efficient conventional ICE internal combustion engines, and of course also develop hybrid and fully electric powertrains. And the onus is largely on the tier suppliers to invest in and develop these powertrains – especially for hybrid and electric where OEMs do not have the in-house experience or expertise.

This huge transition to electrification has clear implications for tier suppliers in terms of their product focus and product mix, their tooling and also their expertise. For example, more companies are having to hire and train more software engineers rather than mechanical engineers as most would be accustomed. We think it is harder for tier suppliers to attract and develop this talent as well compared to OEMs.

Where would you expect more consolidation among tier suppliers? In which segments or commodities?

Daniel Harrison: As our analysis has shown, we expect industry consolidation among tier suppliers in areas that are more commoditised or in managed decline, such as for conventional ICE powertrains and basic mechanical components. We have seen that recently with the announcement that BorgWarner will acquire Delphi Technologies.

We also expect consolidation in areas that are highly commoditised, such as seating and electrical wiring harnesses.

If you look at the computer and electronics industry, the hardware builders, such as Asus in Taiwan, are what have been commoditised. What is important is the brand and development expertise. Is that a risk for automotive companies?

Daniel Harrison: I think the fear here is that if vehicles do increasingly become ‘smartphones on wheels’, then this shifts the emphasis and value chain away from conventional manufacturing and towards electronics and software specialists – such as Apple, Google, Tencent, Sony, etc. Consumers may become more concerned with the version of software on the touchscreen on the infotainment system rather than the performance, engineering and design of the car. Traditional OEMs could potentially be side-lined and usurped by the cash rich tech giants.

Christopher Ludwig: I’m also not entirely convinced that OEMs or tier 1s will so easily monetise connectivity and data compared to tech companies. The early ventures of tier 1s and many OEMs into things like shared mobility have not proved very successful so far.

There are plenty of examples where EV startups are turning to contract manufacturing, focusing more of their resources on technical development, software and design than production assets – Nio, Xpeng, Canoo and Fisker to name a few. It does raise questions over whether the primacy of manufacturing will decline in the automotive sector.

However, automotive manufacturing is still so complex, high volume and capital dependent, with many regulatory, technological and quality requirements. The idea that this can so easily be commoditised – even for simpler to assemble EV platforms – is somewhat overblown. Startups go in for contract manufacturing for faster launch and lower capex, at least whilst their volumes are low. With any scale, they might well change and build their own factories. And companies like Weltmeister in China, and Rivian and Lucid in the US will have their own facilities – with Rivian following the Tesla model of taking over and revamping an existing car factory.

I was intrigued by some of the early discussions about how the FCA-Foxconn joint venture to build electric vehicle in China. Foxconn, which of course builds the iPhone, was quoted specifically as saying that it didn’t want to get into vehicle assembly, even though manufacturing is what it does for Apple. Rather, it wanted control of components, supply chain and design. That might say something about where it sees value-added opportunities. But it also shows that barriers to entry for vehicle manufacturing remain high.

Watch the webinar in full below:

Can automation help to reduce tier supplier margin compression?

Daniel Harrison: Yes, of course this could be an answer in some cases. The reason we didn’t find that this issue was identified in our research was that firstly, in most cases, large tier suppliers already have high levels of automation, a trend that has increased over the past 30 year or more. Another issue is that any further automation would require considerable capital investment and time to implement and the returns on that investment may not appear for many years.

Christopher Ludwig: Across our editorial coverage, notably in AMS, we definitely find plenty of examples where tier suppliers are increasing automation. As Daniel said, I’m not sure this is an immediate way to mitigate margin pressure. But some new product lines and technology will lend itself to more automation. We can see that as more companies adapt or invest in facilities to build electric motors and battery packs, with OEMs and suppliers introducing new automation and modular production measures.

In other cases, new technologies allow for more automation. There are many examples, but one recent one that interested me was brake-by-wire, for which Italian brakes supplier Brembo has increased automation.

Do you see components ‘standardisation’ as a main trend in the future?

Daniel Harrison: To some extent, yes. The increasing examples of platform sharing indicate an increasing standardisation of the basic rolling chassis of a vehicle. OEMs are not just consolidating platforms across their own brands and model lines, but also sharing or jointly developing platforms. Examples include VW and Ford, Rivian and Ford and now Canoo and Hyundai. PSA’s planned merger with FCA is also expected to rationalise platforms.

The design, branding and user experience can then be built upon the platform by the individual brand to create a unique design vision. Standardisation usually has the effect of lowering costs, which is great for the volume OEMs, but constrains innovation at the same time. So, it’s a balancing act. For example, even within supposedly ‘commoditised’ EV powertrains, there is still a huge range of different products and battery technologies that are not compatible, and that innovation is healthy to push the technology forward.

When you talk about the opportunity for suppliers to become more ‘full service’ or ‘tier 0.5’ suppliers, isn’t that likely to be specific to only a small few?

Daniel Harrison: Of course, the tier 0.5 model is only applicable to some suppliers who are positioned in such a way that they could potentially grab more of the value chain or form closer alliances with OEMs. Clearly, if you are JTEKT Corporation which only produce bearings, it would be unrealistic to suddenly diversify into ADAS and autonomous software.

However, more diversified suppliers, such as Bosch, are developing complete ‘turnkey’ powertrain solutions that OEMs can simply fit onto their platform, rather than sourcing everything from a range of suppliers, such as the electric motor, the transmission, the battery pack, the cooling system, battery management system, etc.

Christopher Ludwig: Clearly not every supplier can turn in itself into a Magna, nor does every supplier have the historical pedigree that links it so closely to a carmaker’s R&D operations. However, in some ways tier 1 supplier consolidation will have the effect of creating more integrated suppliers. For example, in combining Calsonic Kansei, a supplier with historical links to Nissan, and Magneti Marelli, which had been owned by Fiat Chrysler, into Marelli, the private equity-backed company had said it would become more of a tier 0.5. It is already looking to play that role in electrified powertrains and lighting, and will look to do so elsewhere through acquisitions, for example in sensors and autonomous driving features.

The other thing to note that a full-service supplier doesn’t need to build an entire vehicle or focus only on the most high-value technology areas like powertrain. We are seeing more tier suppliers integrating their engineering, production and delivery into complete module solutions rather than a ‘build to print’, whereby the OEM effectively supplies the IP and directs supply. We’ve seen this in parts that range from wiring harnesses from Yazaki to battery cases, engineered and built by the likes of Gestamp through new methods. These may not be tier 0.5 suppliers, but they are taking over more product design, manufacturing and service areas.

With so much tech and software in the vehicle, how much of a greater role do you see for electronics and infotainment suppliers? Will they take a greater share and influence?

Daniel Harrison: The increasing electronics content of modern vehicles clearly changes the balance of power. Together and sometimes directly connected to electric powertrains, the growth area in automotive is undoubtedly with electronics, software in infotainment, connectivity and autonomy.

The recent Sony Vision S prototype is a case in point. The Sony branding, the infotainment, electronics, and sensors are all supplied by Sony. As a consumer electronics company, Sony naturally put the UX most prominently. The mechanics of the platform and engineering of the vehicle were somewhat secondary. As we discussed in the webinar, tier suppliers including Magna and other carried out engineering and prototype building.

Who is driving more innovation in the automotive market today: OEMs or suppliers?

Daniel Harrison: We think it is primarily tier suppliers. Part of the reason is that tier suppliers’ margins are being squeezed is that they are primarily being required to develop the hybrid and electric powertrains for the OEMs. It’s not entirely tier suppliers of course, and there are many examples of OEMs leading innovation – for example, being involved in EV battery module design and pack assembly.

Christopher Ludwig: With 65-70% of the value of vehicles brought in by suppliers, collectively the suppliers do own more. However, OEM control and direction over this is quite significant. If you look at some products, OEMs will even control the tier 2 and tier 3 suppliers to a tier 1 under ‘directed supply’ arrangements.

Regardless of who pushes more innovation on a given product, it is worth pointing out the obvious: OEM-tier suppliers have a highly symbiotic and co-dependent set of relationships. And as we move deeper into new technology, whether electrification or autonomous vehicles, the collaboration is only increasing. You can see that with joint OEM-tier supplier development teams, for example between Daimler and Bosch.

One of the biggest challenges is finding a decision maker within an OEM or tier 1 who is willing to champion the savings we are proposing even if it throws a negative light on them or their department that these costs have not been identified sooner.

Christopher Ludwig: We certainly can confirm hearing similar frustrations from other service providers and suppliers in the industry when it comes to implementing potentially cost-saving systems and solutions. At some manufacturers, budget pots are still quite siloed and getting projects to the right level to account for savings across functions can be difficult – even if most supply chain and purchasing executives say that they account for total enterprise cost. We see this as a common challenge in areas like packaging or warehousing, where companies are not always able to balance investment costs between plants and logistics.

But if you’ve got good ideas and systems, don’t despair. If the margin compression and challenging economic climate for many tier suppliers does anything, it might focus minds more to where true savings can and indeed need to be made, regardless of internal silos. As I mentioned during the webinar, although our conversations with OEMs and tier suppliers reveal a very clear restriction on projects that don’t deliver a very short ROI (often 6-8 months), in parallel there are more projects making more significant digital progress. Examples include the broader efforts of OEMs like Volkswagen Group with Amazon Web Services and BMW with Microsoft to standardise their manufacturing IT systems in the cloud, including connections and links with tier suppliers.

We have also noted a number of tier suppliers also making transitions to cloud enterprise resource planning (ERP) or upgrading manufacturing execution systems (MES), including the likes of Faurecia, Visteon and Adient. For logistics, more tier suppliers are also investing in transport management systems.

The shift to electrification is also prompting other necessary investments. For example, in more integrated product lifecycle management systems (PLM) to connect vehicle design, engineering changes and prototyping together with manufacturing and sales.

Can you highlight on why there is decline sales in Asian market like India?

Christopher Ludwig: The question is a little beyond the scope of what we’re trying to cover here. Broadly speaking, the current declines in India and some other Asian markets stem from a variety of factors, some related to the slowdown in China and the overall poor global trade performances. But the most prominent issue is a credit squeeze and loss of confidence.

In India, credit is particularly under strain as the economy has slowed and unemployment rises. Many businesses are holding back investment. All of this has a knock-on effect for automotive, where sales have been hit particularly hard. That is inevitably also giving automotive suppliers in the country a tough knock.

But that doesn’t change the longer-term positive outlook for India and South-East Asian markets. The Indian vehicle market is still likely to head towards 5m units – even if that now comes at the end of this decade rather than the beginning. Production and sourcing in India are competitive. Most global suppliers have a presence in the country and according to Mckinsey, the components industry averaged 9% annual growth for ten years up to 2019. There has been progress on quality and technology. India’s IT industry complements the supply chain as software and engineering development are more closely entwined with supplier products, which could bode well for supplying high tech vehicles for both the domestic and export markets.

While much of South-East Asia is currently struggling, Vietnam has been a particularly strong performer. There is more investment in manufacturing here, including the launch of a new OEM in Vinfast, with the supply base following. Its trade arrangements in Asia and also with the EU, with which it has inked a new trade deal, should strength its export potential further.

Tier suppliers are likely to see shutdowns and contigency measures to manage the impact hit their bottom lines. Read more about impacts to the supply chain here

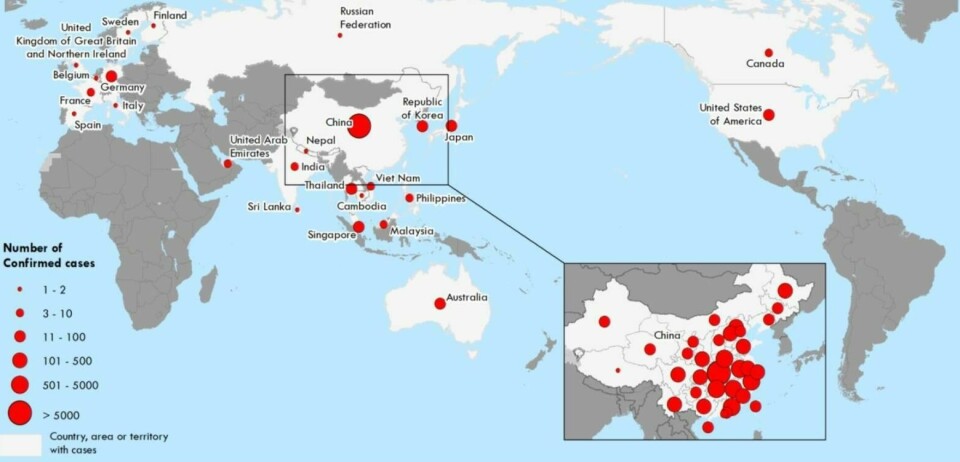

How can international suppliers who supply to China respond to the Coronavirus?

Christopher Ludwig: This is of course a fast-developing situation. We are learning each day about how wide and far the impacts will be, not only for factories in China but also for South Korea, Japan, US and Europe. Some Chinese factories are slowly starting operations again, which could alleviate some issues. But with significant restrictions still in place, supply and output look likely to be limited.

Clearly, suppliers will rely on buffer stock and work with OEMs to rearrange production and organise supply to minimise or delay impacts. But depending on how long travel routes are restricted, or certain factories in Hubei Province or elsewhere in China are completely offline, any contingency is quickly exhausted. We know that suppliers and OEMs are using emergency freight services that they can in the meantime. I suspect that, similar to after other disasters which shut down access to certain regions in Japan or South-East Asia, that many suppliers and OEMs might be caught off guard by just how dependent some of the lower tier supply chain comes out of China. Electronics are a case in point, but it will also hit other commodities. Given how much of the lithium-ion supply chain is based in China and Asia, recent battery supply shortages could worsen.

I don’t think we’re in a position to assess all the outcomes yet. If you look at the impacts from GM strikes in the US last year, you can clearly see how badly some tier supplier financials were hit. If this lasts several months, and China loses hundreds of thousands, if not a million or more vehicles, the impact will be much worse.

Even when the situation is under control, we might also expect a bullwhip effect of sorts, as factories try to restock and catch up demand. That will bring further cost and operational challenges and could hit suppliers with heavy expedited shipping costs to make up demand.

In the medium term, there might be some efforts to diversify supply chains if manufacturers find they were too reliant on China. Depending on the product, the intellectual property and the tooling requirements, however, this cannot always be done so quickly.

As EV investment increases, we’re seeing a host of new battery plant and supply agreements. What role do you see the battery suppliers playing in the value chain, and how will or won’t they work with traditional tier 1 suppliers? Will it be a battle or collaboration?

Daniel Harrison: What we are seeing is that most of the new battery plants and supply agreements are directly between OEMs and battery suppliers. In most cases, the major tier 1 suppliers are not involved in the battery supply, although they are playing roles in the overall electric drivetrain.

What we expect to happen is that as hybrid and fully electric vehicles become a growing proportion of the sales mix, that battery suppliers will inevitable move up the list of tier suppliers and potentially enter the top 20 tier 1 suppliers.

So for now, battery suppliers are in a very strong position, and we expect them to compete with existing tier suppliers.

Do you see a risk that battery powertrains themselves will be commoditised? Or will suppliers really be able to distinguish themselves here?

Daniel Harrison: The evidence I have seen is that battery cells are not commoditised. There is actually quite a variation in price, performance, size and weight.

For example, CATL cells are considered cheaper, but have a lower energy density, and are therefore used for lower cost entry levels vehicles especially in China.

LG Chem and Panasonic batteries, meanwhile, are considered to have a higher energy density, and more reliable, but are more expensive.

There are also emerging niche players. We recently spoke to AGM Batteries, for example, and we can see space in the market for high-performance batteries for specific applications, such as a supercar, or a vehicle for cold environments.

We think batteries are far from being commoditised. Plus, with supply shortages possible as production ramps up, these suppliers seem likely to retain significant pricing power.