VW and Ford invest in flexible production for an uncertain future

The speed of change in the technology of cars, electrification and the introduction of advanced software is requiring new manufacturing equipment and is making expensive old machines redundant, but exactly where the industry is going next is hard to predict. More flexible manufacturing is the answer for Ford and VW.

To avoid having to re-fit factories more often and in orderto make upgrade work count, manufacturers are looking to introduce more flexibility in their production and are re-evaluating their strategies for insourcing and outsourcing, said experts from Volkswagen, Ford, Renishaw and Atlas Copco at last week’s AMS Livestream on electrifying production.

“The speed is picking up more and more,” said Danny Auerswald, plant manager at Volkswagen’s Transparent Factory in Dresden. “In the past you had a product lifecycle that was basically seven years, with one big facelift after three or four years. Now you have constant changes, not only driven by the hardware, but also, and especially the software.”

It’s something that Ford is also feeling and Chris White, electrification manager, manufacturing engineering, added that the switchover to EVs makes the payback for new equipment much more uncertain. “If I were to automate a traditional assembly line for an engine or a transmission, I can pretty much rely on that being there for the next 15-20 years,” he said.

For EVs and hybrids, the technology is changing so rapidly that you can’t be sure that equipment will still be relevant after 10 years. It is therefore essential to build in flexibility, but it still involves more risk than before.

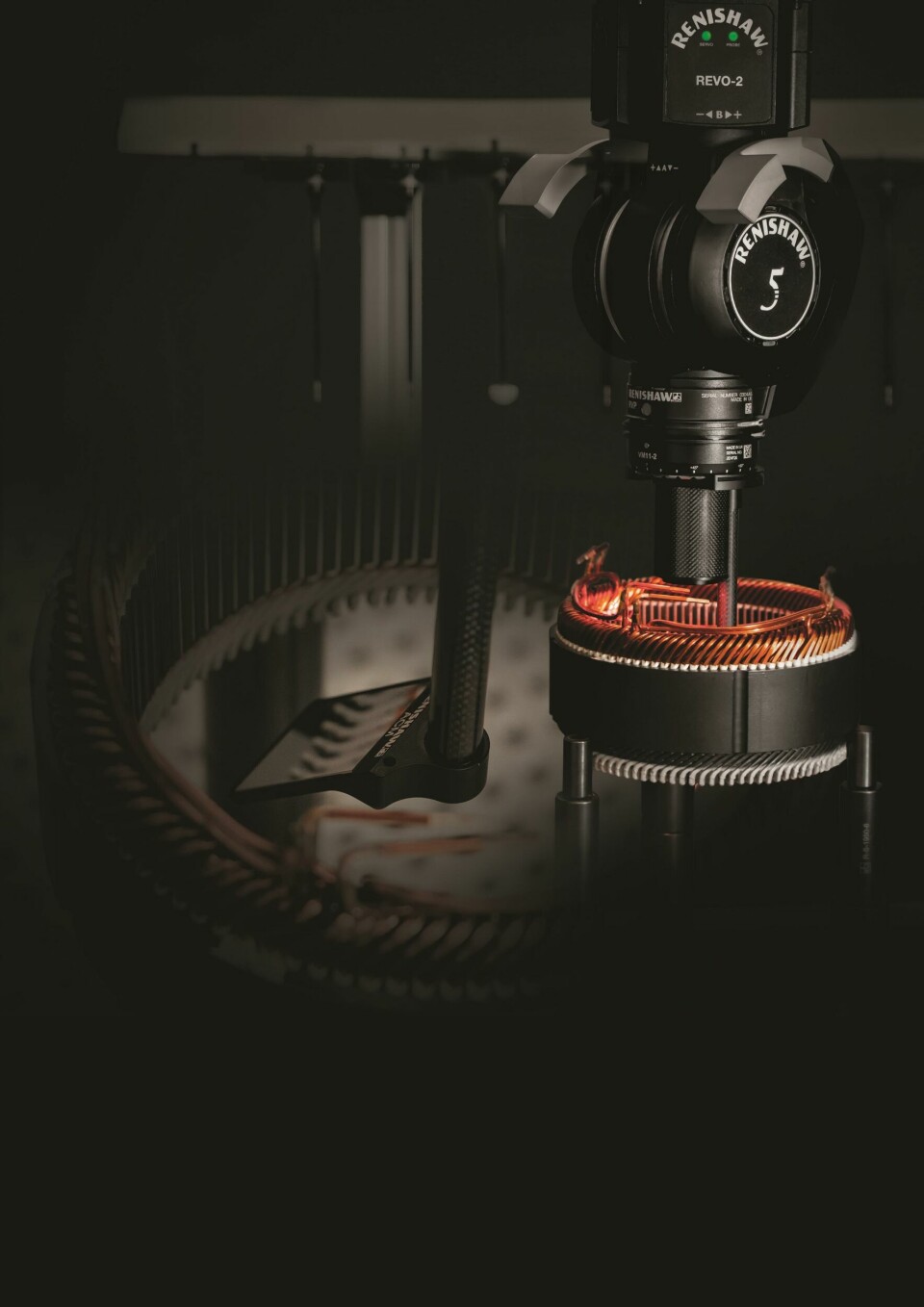

According to Gareth Tomkinson, business development manager at Renishaw, equipment needs to be capable of being repurposed with minimal changes or additional investment, because as well as shortening model cycles, customers’ cars are very customised. All of this is a big challenge, as “the most efficient way of repeatedly making the same component is to use dedicated tools and processes for each individual task,” he said.

This philosophy is also espoused by Ford, and White says that the company has spent a lot of time figuring out how equipment might be repurposed in the transition to electric, an exercise that is greatly helped by digital factory modelling.

Modularisation and outsourcing

The solution, or at least part of it, is to scale back on the product variety and move towards modularisation and novel ways of selling optional equipment to customers.

The Volkswagen Group was an early adopter of shared architectures with the MQB platform and is carrying that into the electric age with its MEB platform for its mainstream electric vehicles.

Auerswald said that this also simplifies production, as everything is designed around the battery, and the sequence of assembly becomes homogenised across models. This in turn allows the conveyor system to be optimised and manual handling to be reduced.

This standardisation does require a different approach with suppliers. For its MEB-based models, VW has started to rely more on suppliers to assemble larger modules. To make that work, they need to be involved early on in the production planning process and relevant data needs to be shared with them, which can be an occasionally sensitive issue.

James McAllister, general manager for ACTIAS at Atlas Copco confirmed this view from a supplier point of view, adding that the formation of long-term partnerships collaborations in in key technology areas is critical to be successful. He said: “It simplifies the procurement process, and leads to faster time to market for the end products. And I think most importantly really, it facilitates a good R&D collaboration between the supplier and the OEM, so that the products are actually aligned to what the OEMs needs.”

With such an approach, the only thing that is really different between models is the size of the vehicle, even though the appearance to the customer is different. Where Auerswald sees big differentiation between models is in the software. He said that overall, he sees a move to less complexity thanks to the simpler mechanical layout of EVs, but that handling all the different electronic modules and making sure the different car models can be easily built on the same line is the bigger challenge.

Another concern is making sure that you have always the right software version coming from the supplier and that it matches with the right hardware version coming from the supplier. “And then if you want to do the whole software set up, everything needs to match together so I think that’s the biggest driver at the moment when it comes to complexity,” he added.

A final change removing mechanical complexity in assembly, but adding software complexity, is that vehicles get the option of over-the-air updates once they are in use: “There are already some scenarios where the customer will get a fully equipped car, and then only pays if they use a certain item like LED matrix lights – say they make a big trip and want better lights, and then afterwards they just get rid of it virtually, and not pay for it anymore.”

Virtual trial runs

In order to make production planning less perilous, both VW and Ford have looked towards virtual tools. Ford’s White said that infrastructure work usually has long lead times attached to it, and that it used to not be unusual to find that the complex building blocks that make up a facility don’t fit together as intended when the time came to physically outfit a plant.

Today, a lot of the planning work can be done digitally. Adding all the necessary assets to the system such as machines and parts involves some work, but having a digital clone of the factory ultimately saves a lot of time, as any alterations can be tested in the virtual world before any expensive and time-consuming work is undertaken.

White explained that reconfiguring a factory in the virtual world doesn’t cost anything, and “it’s a quick answer to whether you can do things or not. Trying it out obviously is not an option in our business in a real physical factory. So it’ll help us verify changes and make sure that we can make them very quickly.”

One key concern for Ford going forward is the size of the cars and components as they pivot to EVs. He said that they had that process largely down with engines, but with batteries, and electric motors, there is still some work to be done in predicting how the product envelope is going to evolve and suit any flexible production process that might be implemented.