How battery and electric motors and EVs are reshaping the European automotive supply chain

The automotive industry is in a major shift with EVs reshaping the supply chain. Challenges and opportunities include replacing traditional components tied to combustion engines, new players in the battery market, disruptors facing tariffs, and the looming influence of China in Europe; all adding new layers of complexity.

In a separate article we have looked in detail at the changes in manufacturing arrangements at Stellantis, Volkswagen and Renault; the three companies with the widest and most complex manufacturing networks in Europe. Here we look at developments in the nascent battery and electric motor supply chains and the potential for reshoring, and whether new VMs might yet change the European production landscape even further.

The mother of invention: how battery and electric motors are creating a new supply chain

The switch to EVs demands a new supply chain. Petrol and diesel engines and their associated components are no longer going to be needed, except for spares. With internal combustion engine (ICE) sales already declining, the European Automobile Manufacturers Association (ACEA) has recently projected EVs will make up 40% of the European market by next year. Along with fewer and ultimately no ICE engines being produced, EVs will naturally dispense with conventional components from transmissions and clutches, to engine cooling systems and exhausts, to name a few. Suppliers of these parts will consequently lose business and need to develop new areas of expertise or risk disappearing.

To adapt to this quickening market change, car companies are converting transmissions factories and existing plants to manufacture electric motors. For example, Ford is doing just this at Halewood in the UK where its transmissions plant will become an e-motor factory; JLR is adding e-motor production at Wolverhampton; and the Renault Cleon plant is switching from petrol engines to electric motors.

For batteries, something which European vehicle companies have no deep experience of, entirely new suppliers have entered the market. LG, SKI and Samsung are the Korean entrants, with Panasonic from Japan. But the big change in terms of supply chain origin is the arrival of the Chinese, with BYD, CATL and Envision (the key supplier to Nissan and Renault) absorbing an increasing share of European business.

Gotion of China, is another smaller supplier which is developing a European presence in association with Volkswagen.

To begin with, as EVs first emerged, European VMs appeared content to let the established players from Asia and some new entrants, notably Northvolt (a Scandinavian new entrant with backing in terms of guaranteed orders from BMW and Volkswagen), take the majority of this growing market. But as the switch to EVs accelerated and government regulations accelerated the trend, the VMs realised they could not afford to give up control over this key part of the vehicle value chain.

Currently a fully assembled battery can represent 50% of the value of a vehicle’s bill of materials, and this – allied to the inevitable loss of jobs in in-house engine and transmissions production – meant that the VMs had to adopt a different approach.

Volkswagen decided it would build six battery factories - or rather six battery cell factories in Europe. Three of these have been committed to in Sweden (with Northvolt), in Germany, and in Spain, but the other three are currently on hold as the company has switched attention to North America, where significant incentives for battery assembly cell production are on offer from the US government through the oddly named Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

This is really a huge industrial subsidy facility, worth US$4 trillion across a variety of industries. Although Samsung and other Korean companies in Poland and Hungary have retained some existing battery contracts with the VW group, most of the new contracts for VW will go to its new in-house operations which operate through a new subsidiary, PowerCo, which may also be floated-off in the future.

Similarly, Stellantis has decided to take control of most of its battery cell production through a new company, ACC, a joint venture with SAFT and Total, and Daimler has also taken a stake in this venture. The first cell factories will be at Douvrin in northern France and Kaiserslautern in Germany, - both former components plants. Intriguingly, perhaps reflecting the costs and time required to develop its own all-new supply chain, Stellantis has announced it will bring Chinese supplier, CATL, into Europe in a separate JV to supply “cheap” LFP (lithium iron phosphate) cells for vans and entry level A- or B-segment cars.

This will begin operations in later 2026 or 2027. The ACC cell factories will focus on making more expensive NMC (nickel manganese cobalt) cells which will be used in the C- segment and above.

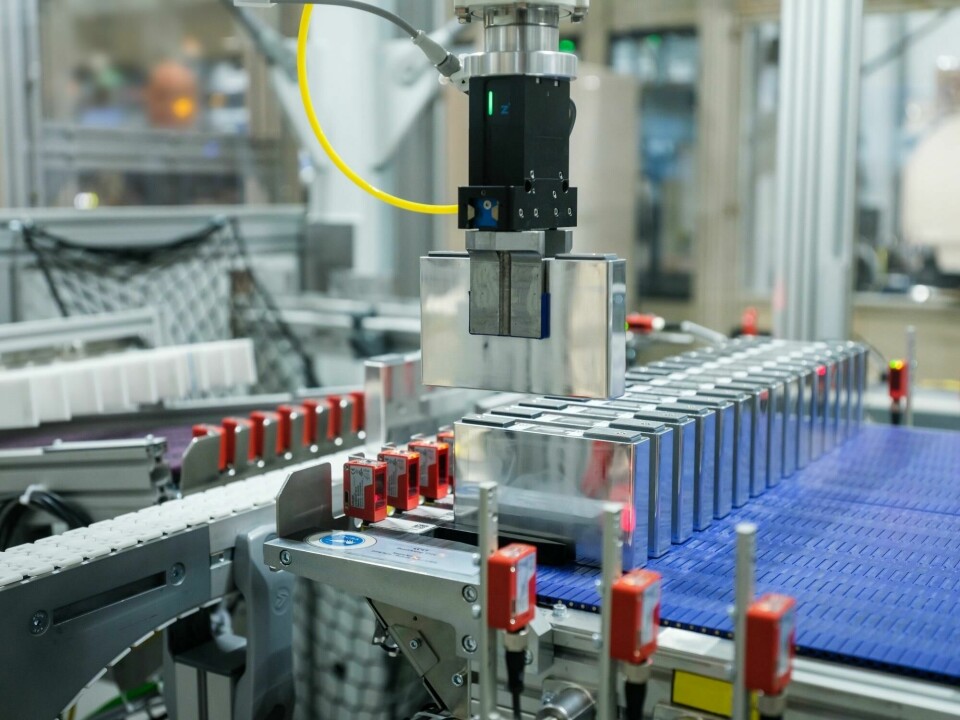

A key feature of the new VW and Stellantis supply chains is that the so-called gigafactories will only make cells, which will be shipped to vehicle plants, or to localised assembly facilities, for assembly. This pattern is being repeated at most European vehicle plants producing EVs; Volvo assembles batteries for its EVs at its car plant in Belgium, with cells coming from independent suppliers; Stellantis’ electric vans made in Spain take cells from China and assemble them in Spain, and the Stellantis electric van plant in the UK also currently uses cells from China, with assembly into modules taking place in Spain before the modules are shipped to the UK for assembly into complete batteries.

Falling in-line with this supply-production infrastructure, Audi Brussels takes cells from eastern European sites of Korean cell companies and assembles them into batteries in a clean room facility in Brussels, which it also does at its Neckarsulm and Hungarian plants which make a variety of e-tron models. Renault and Nissan are exceptions to this rule, as they use fully vertically integrated battery cell and assembly operations close to their Douai and Sunderland sites, run by AESC Envision.

Ford’s approach to battery sourcing is to set up joint ventures – with Korean suppliers in Europe –although it has scaled back plans for a battery plant in Turkey as it now expects ICE or hybrid powered Transits to dominate for longer than originally thought, reducing the immediate need for a full-scale battery plant in the country.

BMW (which will undertake key finishing processes for its cells in house in its Leipzig plant) uses external suppliers, notably CATL, to supply semi-finished cells which are completed in Leipzig and sent onto the vehicle plants for assembly into complete battery packs.

Reshoring and the impact of rules of origin protocols

Batteries and electric motors are not only creating a new supply chain at the tier 1 level, i.e. for delivery into the car plants, but further back into lower tiers as well. While VMs have always debated whether to source parts from close by to the car plant (and pay a premium for higher labour and other costs in Europe for doing so) or from further afield - in lower-cost, mostly Asian locations.

For batteries, the new supply chain and new suppliers operating here are most developed in Asia where the EV market has also gained maturation. Although the critical minerals for batteries (nickel, lithium, cobalt and manganese for example) come from Africa, Chile, or Australia especially, the key, value-adding stages, i.e. processing and production of components, take place mainly in China and Korea.

The political and practical significance and risks of being reliant on China for key processing stages and components is widely recognised, and both the EU and the US government have decided this state of affairs cannot continue.

In the US, the IRA offers significant financial support for vehicles with batteries made in North America, with suppliers and VMs alike encouraged to locate key processing tasks and indeed, mining operations in North America. The EU is trying to do the same and one of the ways in which it has chosen to do this is through the rules of origin provisions in the UK-EU TCA following Brexit.

These provisions require 55% of the content of vehicles made in the UK or EU and sold in the other market (i.e. crossing the UK-EU border) to be sourced from within the UK or the EU in order to qualify for tariff free access. In addition, they also require a rising proportion of the value of the battery in an EV to be sourced from the UK or the EU. From January 2027, to avoid tariffs, EVs will have to use what is called an originating battery, i.e. one either from the UK or EU and for which 70% of the value of the battery itself comes from these regions.

This will be impossible to achieve without battery cell producers being able to source key components, especially cathodes (and potentially anodes) in the UK or EU. Currently, while there is some cathode production in Europe (e.g. by Umicore), there is not enough capacity to supply all the cells which are due to be made by 2027; there is a lot of investment in this area, as well as in other battery components, but whether it will all be on stream by January 2027 is open to debate.

Vehicles without a qualifying battery from January 2027 will face a 10% tariff when crossing the UK-EU border. The EU had hoped that by building this ruling into the UK-EU TCA, they would encourage investment in sufficient production capacity to avoid the tariff being applied.

Tata’s decision to locate a battery cell plant in the UK and Nissan’s commitment to greatly expand its battery capacity in associate with Envision to supply its new 3 model electric vehicle line-up, as announced in November 2023, are direct responses to the UK-EU TCA provisions on batteries. But these cell factories require cathode and other battery components to be made in the UK or the EU to comply with rules of origin protocols; however, detailed plans for sub-suppliers in this new supply chain have not been made or made public if they exist already.

Ahead of the 2027 rules coming to force, there was the issue of impending changes to local content rules which were due to come into effect on January 1, 2024; these do not officially mandate a local battery, but they do require 60% of the value of the battery to be sourced in the UK or the EU for an EV to avoid a tariff when crossing the UK-EU border.

Leaving aside the practicalities and costs of the administration involved in proving compliance with these rules, it was widely recognised that neither the EU nor the UK has sufficient capacity in the battery supply chain to meet this requirement from January 2024. Now the European Commission has proposed a delay to the implementation of this ruling until 2027.

There is limited room for VMs to reshore much more of their supply to chain in order to comply with these rules of origin requirements; most of what it is economic to make in Europe is made here already and where Europe is too expensive, e.g. for wiring harnesses, much of this actually takes place for European VMs in the PEM (Pan-EuroMed) area, which includes North Africa. This is in turn effectively creates a bigger area for local content purposes, with components sourced from Morocco and Turkey allowed to be counted as EU content when necessary.

Because of limited potential for reshoring much value in non-battery components, maximising the value of battery content within Europe is necessary. It is for this reason that potential lithium sources in Europe are being seized upon as potential saviours of the industry – because if lithium or other key battery minerals can be mined in Europe (sources exist in Cornwall in the UK, in Serbia and parts of Germany) then minerals processing will follow and this will in turn make battery cell component production, especially cathodes, economically viable in Europe more quickly than otherwise.

The question regarding European critical mineral sources is whether they are sufficient, and it is likely that sources from further afield, Australia and Chile for example, will still be needed; what matters then will be the establishment of mineral processing in Europe, rather than relying on minerals processing in Asia, with all the attendant carbon costs this practice engenders.

The impending CBAM (carbon border adjustment mechanism) rules may well be the final requirement to force localised cathode and anode production for European EVs; EU (and presumably UK) rules will force companies, in automotive and other industries, to fully account for the carbon content embedded in the manufacturing of their products. Local mining, processing and battery component production within the UK or the EU will clearly produce less carbon – and generate lower carbon costs – than mining in Australia, processing in China and then transporting finished or semi-finished products halfway around the world.

The economics of battery production may encourage a new supply chain to be located in Europe, but it may be that it is a new regulatory environment which will enforce it in reality.

The impact of the Tesla and the Chinese VMs

Finally, returning to the VMs, there is the issue of the new entrants and how they may change the structure of the industry in Europe. Clearly the biggest and most disruptive new entrant is Tesla – it is now producing vehicles in Berlin, after many delays; it produces the Model Y, intriguingly using cells from BYD in China rather than its own cells. Ironically plans for Tesla to make battery cells itself in Europe have been delayed with the company expanding cell production in the US for the moment; ultimately it will restart plans for cell production in Europe, but the timing for this is not known.

In fact, it wants to boost its European vehicle output towards 1m a year (making Berlin into the biggest car plant in Europe) rather than move into battery production – in addition to the current Model Y crossover, additional models, the Model 3, the expected smaller Model 2 and other models yet to be confirmed may also be made in Berlin.

The first Chinese VM meanwhile to have its own full car production plant in Europe is expected to be BYD; this company already makes buses in Hungary and there is widespread expectation that it will announce a car plant and a supporting battery plant in the near future.

German press reports in November 2023 effectively pre-announced this but it has not been officially confirmed by the company. This would likely involve production of around 200,000 or more B segment and/or C segment vehicles, intensifying the pressure on European VMs in the most price-sensitive, lowest margin areas of their business.

After BYD, it is likely Polestars will be made by Volvo, in Sweden and the new Volvo plant in Slovakia, while the other Volvo plant, in Belgium, has been linked with production of models for another Geely brand, Lynk&CO. This had been expected to be a reality already, but it is now likely to happen by the end of the 2020s.