Mission to a million

Nick Gibbs reports from a renowned Russian plant that, despite a challenging domestic market, aims for a return to the high volumes of its colourful history

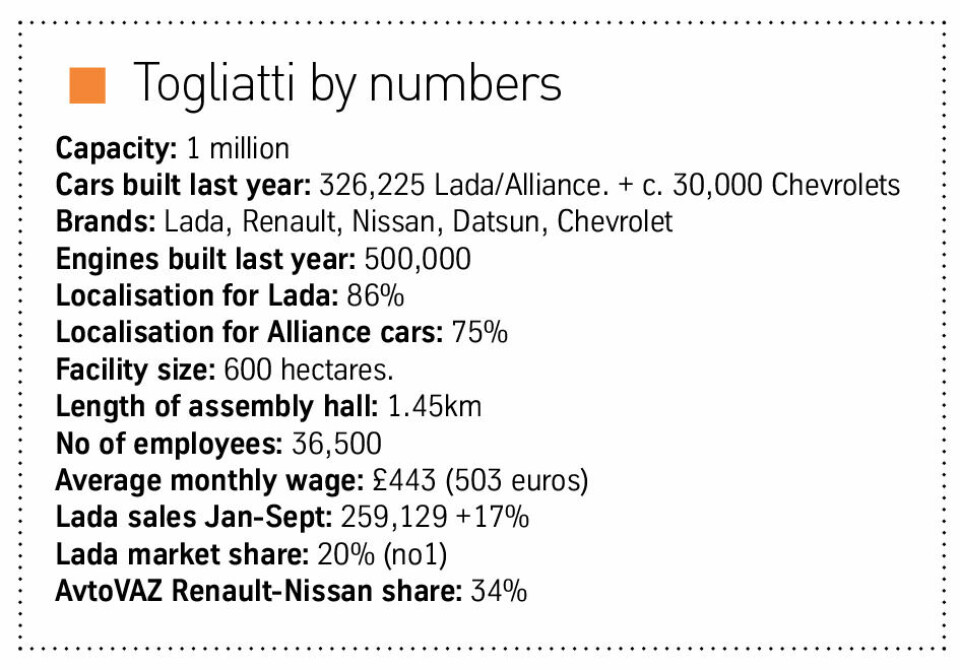

On a list of the world’s iconic car factories, Russia’s Togliatti, production centre of Lada cars, would make many people’s top 10. This vast plant, situated on a bend of the Volga river 1,000km east of Moscow, was built when Soviet protectionism could support a workforce of more than 100,000 making up to 1m cars a year.

Post-Soviet times have not been so kind. Lada’s parent company, the loss-making AvtoVAZ, has struggled to impose the manufacturing discipline and lean production methods needed to protect itself against faster moving rivals operating without the same legacy burden.

But there are signs that might be changing. A visit to this 600 hectare facility shows the scale of the task but also that AvtoVAZ and its owner, Renault Group, are slowly making the improvements needed to make company profitable and ready to do battle with Lada’s current biggest rivals: Hyundai and Kia.

The Italian connection

The name Togliatti doesn’t sound very Russian, and it isn’t. The city was named for the leader of the Italian Communist Party from 1927, Palmiro Togliatti. The close Italian connection extends to the cars made there – the first model to roll off the production line in 1970, the three-box VAZ-2101, was the result of a collaboration with Fiat and is a close copy of the Fiat 124 saloon.

This city of 700,000, not far from Samara, remains hugely dependent on AvtoVAZ. The car firm built kindergartens, schools and sports halls among other facilities, and while these have since transferred to local authorities, the city’s fortune rises and falls with AvtoVAZ. Combined with its smaller plant in Izhevsk, 570km, to the north-east, its dealer network and its suppliers, AvtoVAZ is responsible for the livelihoods of around 2m Russians, the company reckons.

The turnaround for Togliatti, or the Volzhsky Automobile Plant to give it its proper name (Volzhsky referring to the Volga river, and is the second V in AvtoVAZ), started officially in 2008, when Renault first began investing in the company. Since then Renault has sunk e1.7 billion ($1.9 billion) in a bid to make it fit for modern Russia.

Modern Russia, however, does not make it easy. The local car market has collapsed twice since 2008, falling from 2.8m in 2008 to 1.4m in 2009, before rising to 2.8 million again in 2012 and then collapsing again to 1.3m in 2016. In that time Lada has seen its market share swing from a high of 29% in 2010 to a low of 16% in 2014. Now the company is running at a consistent 20% share over the past three years, a figure that AvtoVAZ CEO Yves Caracatzanis says he’s happy with. And the wider market is improving again, with sales expected to hit 1.8m for 2018, which would be a healthy improvement of 13% on the year before. Caracatzanis predicts the market could reach 2.5m by 2025 at least.

There’s still plenty to do, though. “We are at 20% now but competition is tough,” Caracatzanis says. A brief return to profitability in the first half of this year won’t translate into a full-year’s profit, he believes, because of further big spending requirements. “We know we have a huge investment to do to renew the brand and to continue the modernisation of the plant. And we still have a huge debt,” he admits. The mid-term plan, he states, is to profitable after 2021.

The big push came in 2012 when Renault created a joint venture with AvtoVAZ’s main shareholder and overhauled a production line in Togliatti to produce Lada, Renault and Nissan cars on Renault-Nissan’s low-cost B0 platform (the one underpinning Dacia cars). But they needed someone to oversee the company, and in 2013 Renault hired, in the position of CEO, Bo Andersson – a Swedish ex-army officer who’d recently made a name for himself by turning around another struggling Russian automotive company, GAZ Group.

Andersson’s tenure lasted less than three years after he clashed repeatedly with unions and suppliers in a struggle to modernise Togliatti. In a 2015 interview, Andersson said the job was “10 times more difficult” than his Herculean achievement at GAZ. He had slashed the AvtoVAZ workforce by 27,000 from the 75,000 total when he arrived, but froze job cuts a year later to work on suppliers. “This year I can only take on one war, so I said I would take on the suppliers,” he said at the time.

That fight went all the way to President Vladimir Putin when Andersson, a former GM purchasing chief, confronted local suppliers for a litany of problems, ranging from inadequate logistics, poor quality, bid-rigging and even selling aftersales parts directly to dealers. The suppliers, used to their cosy relationship, retaliated by shutting down production and a group of 15 complained to Putin himself.

Andersson, tasked with developing a a more modern B-segment car that would appeal to a urban audience away from Lada’s more rural customers, turned instead to local subsidiaries of global suppliers, as he had at GAZ. He was probably right, but the situation was so tense that his departure was really the only solution to defuse the anger.

His replacement, former Dacia head, Nicolas Maure, calmed the situation by assuring local suppliers they wouldn’t be pushed out. “They became scared they’d lose business, so when I arrived we decided to rebalance the purchasing portfolio,” he said in August. Maure, since promoted to chairman of the Eurasia region for Renault Group, assured local Russian suppliers they would always have 50% of the localised parts business, with global suppliers given the other 50%. “The situation has calmed down,” he said.

Localisation is absolutely key to both AvtoVAZ and Renault’s success in Russia, mainly because the value of the ruble is so volatile. Importing parts is just too risky for the bottom line, when the cars are sold this cheaply; the Lada Granta entry car starts at the equivalent of around e5,200.

Local content is already high at 86% for Lada and 75% for Alliance cars (Renault, Nissan and Datsun) built at Togliatti. The target is 80%. Under Andersson that figure for Alliance cars was just 50% so there’s been a big improvement.

People and plant

As for the workforce, the figure is now 36,500 for Togliatti and 46,500 in total for AvtoVAZ. Caracatzanis says that is right for now. “We are at the same headcount level as the end of last year, but we’ve increased revenue by more than 30%, so the efficiency is increasing,” he explains. Average monthly pay in Togliatti was 38,000 rubles (e503) as of this year, and the average age was 42. Women account for an impressive 40% of the workforce.

Those 36,500 workers made 326,225 Lada/Alliance cars last year, and roughly 30,000 of the long-running GM/AvtoVAZ joint venture SUV, the Chevrolet Niva.

That equates to around 10 cars per person, but if that looks bad then it’s worth remembering that Soviet-era vertical integration. The plant forges iron and aluminium, stamps metal and plastic parts, and has six lines of engine production. It also makes gearboxes and produces painted bodies for Renault’s Dacia plant in Algeria.

Even so, it’s unwieldy – 7,000 people work in maintenance alone. “It’s a demonstration of the Soviet ‘yes-we-can’ attitude, but after that, to be able manage such a huge plant, it’s really really complicated,” according to Jean-Louis Theron, plant manager of Renault’s Moscow plant.

The main assembly hall is a monster – 1.45km long with a 1.35km conveyor. The most modern of the three assembly lines inside is definitely the one building cars on the B0 platform – which includes the Renault Sandero, Renault Logan, the Lada Largus MPV, the Lada XRAY (a small urban SUV developed under Andersson) and the soon-to-be-discontinued Nissan Almera.

This line has recently been overhauled to include ‘kitting’, whereby a set of parts travels with each car to aid efficiency and help out workers. To achieve this, AvtoVAZ ripped out a line between B0 and the far more traditional line where they build the long-running 4x4 (called Niva in export markets, but not to be confused with the Chevrolet Niva, which is produced in a separate building). A third line builds the low-cost Lada Granta and two Datsun models, both on Lada platforms. The other ‘modern’ Lada, the Vesta, is built at Izhevsk.

The B0 line is currently running at five days and two shifts with 3,634 people producing around 189,000 cars a year against a 285,000 maximum on three shifts. Theoretically Togliatti could again produce 1m cars a year, meaning it’s running at less than half its capacity. AvtoVAZ production head, Ales Bratoz, is confident of returning to the glory days. “We hope to hit that again,” he says.