Impacts of global geopolitics on European production

Geopolitical influences on the automotive manufacturing sector are intensifying and becoming ever more powerful. European trends cannot be looked at in isolation; their impact on the ground in Europe have their roots in wider global factors…

When the UK voted to leave the EU in 2016, there was an immediate fear that this would signal the rapid decline of UK automotive production and a shift of production to mainland Europe. The Brexit deal, officially the UK-EU Trade and Co-operation Agreement (TCA), was more positive for UK automotive production than many had feared. The loss of the Honda factory apart, UK vehicle manufacturing has survived intact and following positive announcements at JLR, Nissan and Mini especially, and smaller investments at Stellantis, annual UK production volumes should be around the 1 million level through most of the 2020s.

The positive outlook is underpinned by the UK-EU TCA, which provided for zero tariffs and zero quota trade in automotive vehicles if vehicles met certain rules of origin (RoO) or local content ratios, i.e. 55% UK and EU content combined. UK and EU OEMs were mostly able to meet these rules for ICE or hybrid vehicles. For EVs, the TCA initially required a lower overall UK-EU content level (40%) and also a 30% content level for the battery.

UK and EU OEMs could meet these initial rules but because of a lack of development in the battery supply chain across Europe, there was a serious risk that most of them would not be able to meet enhanced RoO requirements which were due to be applied from January 1 2024. But after significant lobbying by national government and major carmakers, these new battery rules have been delayed until January 1 2027, when battery content will need to be 70% UK or EU-sourced.

The delay is expected to allow time for the battery supply chain in the UK or EU to develop sufficiently to meet these rules. Key to this will be UK or EU production of cathode active material, the highest value part of the battery. The many new battery cell plants being built across Europe should all have local cathode supply by the late 2020s.

The battery content rules in the UK-EU TCA are a very clear example of how trade policy can affect the location of major elements of the supply chain and are driving the investment by OEMs and suppliers alike.

European Commission investigation into Chinese EV subsidies

The Commission’s provisional conclusions of its investigation are that Chinese EVs are being unfairly subsidised. Current understanding is that the EU will impose retrospective additional tariffs on Chinese EVs.

However, German OEMs are opposed to this because they have major operations in China and make significant profits there. The UK government has indicated that it too will respond to Chinese subsidies or dumping of vehicles in the UK with tariffs or similar moves to the EU, although such a move may well be opposed by JLR and the luxury brands which, like their German counterparts, make a significant proportion of their profits in China.

In some ways it may be argued that applying tariffs on Chinese EV imports is akin to bolting the stable door after the horse bolted, not least because the Chinese EV manufacturers are – as noted in the accompanying article – beginning to establish their own manufacturing operations in Europe, and thereby getting around any tariff risk.

‘The security of rail transport and the risk of goods being transported through Russia being hit by sanctions following the invasion of Ukraine is also a major issue’

The threat of tariff increases leads to changes in production location by European OEMs too

And European carmakers with production in China are also likely to change their manufacturing footprints as a result of tariffs which could be applied on Chinese vehicles. Volvo has already decided to move production of its new small model, EX30, from China to Belgium while BMW will switch the current iX3 electric SUV from China to a new plant in Hungary in 2026. There have been suggestions that the small Dacia Spring EV will switch from China to the Renault plant in Slovenia which is being reconfigured to make the Twingo’s electric replacement.

The US dimension…

The upcoming US presidential election and the possible return of Donald Trump may also have a direct impact on trade policy and hit the economics of vehicle production. Trump has indicated that he will introduce a blanket 10% tariff on imports and a much higher tariff on Chinese imports, especially cars. He has mentioned a possible 100% tariff but whether such a tariff would really be applied is open to debate.

At present the US imposes only 2.5% on vehicle imports from most places, although Chinese imports already also face an additional tariff of 25% (introduced by President Trump, effective from May 2019). When this was introduced, Volvo immediately switched US supply of the XC60 from China to Europe and instead supplied any European demand which could not be met by the European factory from China, accepting a 10% tariff.

Meanwhile, President Biden’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) has boosted investment in the production of EVs, batteries and components in the US. The IRA led Volkswagen to direct investment in a new battery plant to North America rather than eastern Europe to take advantage of the tax credit incentives under IRA.

The longer-term implications for European and UK carmakers of IRA remain to be seen. It is entirely possible that the German OEMs with production facilities in the US will decide to invest further in these operations (irrespective of the US president), with exports from Europe falling correspondingly. Audi and Cupra (formerly SEAT) will likely see production in a VW factory in the US to take advantage of IRA incentives favouring US vehicle production, directly impacting European exports and therefore production volumes.

The Middle East conflict

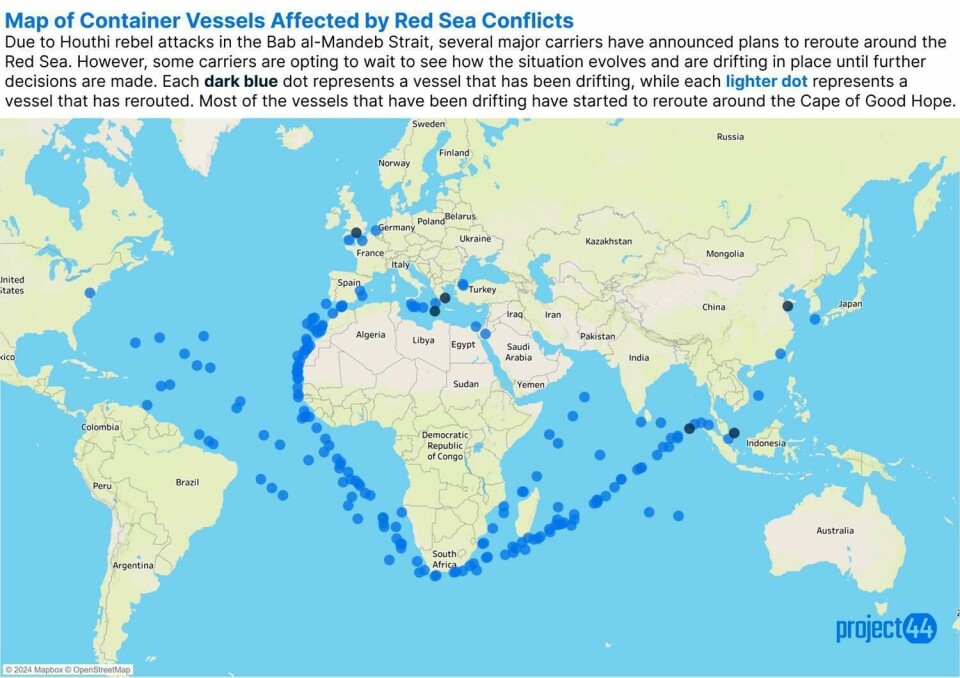

The principal impact of the Middle East conflict to date has been the diversion of shipping away from the Red Sea and Suez Canal to a much longer route via South Africa, adding around two weeks to shipping times from Asia to Europe. The potential cumulative impact of this lengthening of shipping times is huge, especially when additional time costs are added to the extra fuel and labour costs involved, as well as disruption to port schedules.

Some manufacturers have responded by air freighting some components from Asia to Europe. There has not yet been any major disruption to vehicle production as a direct consequence of the Middle East conflict. To prevent shipping issues becoming a long-term risk issue, alternative transport channels are being considered. A Financial Times report in March detailed how some goods from China are now being transported to Europe by rail, through one of three rail routes through Russia. DHL and other logistics companies expect this practice to continue and grow if security of the goods being transported can be maintained. The security of rail transport and the risk of goods being transported through Russia being hit by sanctions following the invasion of Ukraine is also a major issue.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine

When Russia invaded Ukraine, there was a very immediate impact on European vehicle production. Production of wire harnesses in Ukraine, used by several German OEMs, stopped almost immediately, quickly leading to stoppages across most German vehicle plants.

However, this disruption was relatively short lived and within a couple of weeks, alternative assembly lines had been established, including within the Skoda factory at Mlada Boleslav. Some suppliers also switched their production location, from Ukraine into neighbouring countries, including Moldova and Hungary. The disruption to vehicle production was relatively modest and normal production levels were quickly restored.

‘The financial markets have become nervous about funding EV investment’

Tensions between China and Taiwan and the impact on chip production

This is a contingent risk at present, but a very significant risk nonetheless. Taiwan is, primarily through TSMC, the world’s largest production location for semiconductors. If China were to invade, it would likely severely impair global automotive production, and indeed many other industries. It would also indirectly impact its own economy as it would almost certainly lead to sanctions on Chinese exports to many markets.

This risk has led to a boost in investment in semiconductor production in Europe and North America. The EU has established a €43 billion fund to support new chip production facilities in Europe, and individual countries, especially Germany, have set up their own incentive schemes.

One of the major developments in this area is the joint venture between Bosch, Infineon, NXP and TSMC to establish the European Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (ESMC) in Dresden. TSMC will own 70% of the venture, with Bosch, Infineon and NXP each holding 10%.

Financial markets may not fully fund EV development

While battery production is continuing, the financial markets have become nervous about funding all of this investment in the light of the failure of Arrival and the disappointing performance of new EV entrants such as Lucid and Rivian in the US.

Some OEMs had hoped to launch IPOs for their battery or EV units having seen the financial markets fund a number of new entrants. However, market conditions have led directly to VW postponing the planned flotation of its battery cell unit, PowerCo, while Renault has postponed the IPO planned for its EV subsidiary, Ampere.

Will new entrants have a significant impact on industry structure?

The number of successful all new EV companies is remarkably small. Tesla apart, most of the new European or US entrants in EVs have failed or are in severe difficulty, such as Lucid, Fisker and Arrival. The first two may survive, but the latter has gone into administration.

Meanwhile an interesting development in Turkey has seen a new EV company, TOGG, emerge. This Turkish-owned company aims to sell 150,000 vehicles a year, possibly more, across Europe as well in Turkey. German sales should begin this year, and if TOGG succeeds in the long run, it will be unusual, not least because of the failure of new entrants, Tesla apart, to change the structure of the industry.