Navigating the hybrid comeback

Hybrid vehicles return to North America’s production lines as automakers rethink strategy

Automakers that once aimed to skip hybrids and go straight to electric vehicles are now reintegrating hybrids into their North American line-ups. Building “half-and-half” cars is proving technically tricky but strategically worthwhile.

North American factories are discovering that building a hybrid vehicle is essentially like building two cars in one. A hybrid powertrain marries a traditional internal-combustion engine (ICE) with an electric motor and battery pack. This duality complicates production at every turn.

For one, it drives up the parts count and assembly steps. Engineers must find space for both a fuel tank and a battery, an exhaust system and electric cabling, an engine block and electric motors. Designing a platform to accommodate both propulsion systems inevitably forces compromises, what automotive engineers ruefully call ’scar tissue’.

”While economies of scale and clever engineering can mitigate some expenses, a hybrid still demands more labour and materials than an equivalent ICE model”

The result is often a heavier vehicle and a more complex assembly process. Every hybrid requires careful battery integration alongside conventional engine components, necessitating additional tooling and safety measures on the factory floor. From robust battery cooling systems to high-voltage wiring and control software, the extra content that goes into a hybrid can impose a substantial burden on automakers’ manufacturing operations.

All this adds cost. While economies of scale and clever engineering can mitigate some expenses, a hybrid still demands more labour and materials than an equivalent ICE model.

The nuts, bolts and batteries of hybrid vehicles

Managing the battery itself presents further challenges. Hybrid batteries are smaller than those in full electric vehicles (EVs), typically only big enough for a few dozen miles of electric driving, but they endure frequent charge and discharge cycles and must last for years. Ensuring reliable battery performance means implementing sophisticated battery management systems and temperature controls, layered on top of the usual engine management.

Each vehicle rolls off the production line with two powerplants that need to operate in concert, which raises the bar for quality control. Even minor misalignments in assembly can cause vibrations or faults when the electric and combustion systems interact.

In short, hybrids complicate vehicle manufacturing logistics. Automakers must juggle ICE and EV supply chains simultaneously, stocking everything from spark plugs to lithium-ion cells. Little wonder that some carmakers long viewed hybrids as technically cumbersome, especially compared with the relative simplicity of a pure battery-electric design (which forgoes engines and multi-speed transmissions altogether).

Carmakers rethink EV bets as hybrid demand reshapes strategy

Despite the complexities, market forces are pulling carmakers back into the hybrid business. Not long ago, industry strategists in Detroit and Tokyo talked of leapfrogging directly to pure EVs. Executives at General Motors and Nissan were among those who signalled they would bypass the hybrid phase, pouring investment into all-electric line-ups. In practice, that leap proved overly-optimistic.

Consumer demand for hybrids has surged in the past year as buyers seek better fuel economy without the constraints of full electrics. This resurgence has been strong enough to make some automakers recalibrate their electrification plans.

Mary Barra, GM’s chief executive, spent years championing an “all-in” bet on EVs; yet GM now plans to introduce plug-in hybrid models in North America by 2027. Barra still maintains that hybrids are not the endgame (since they mostly act as a bridge to full-EVs, and do not eliminate tailpipe emissions), but concedes they are a pragmatic stopgap to meet stricter regulations and customer needs in the interim.

Nissan leads a hybrid revival as EV ambitions face reality

Nissan has undergone a similar change of heart. An early EV pioneer with its Leaf hatchback, Nissan had focused on battery-electrics while largely ignoring hybrids in North America. But facing a slow EV uptake, the OEM is returning to hybrids with gusto. It will roll out its third-generation e-POWER hybrid systems in models like the Rogue SUV over the next two years, alongside new plug-in hybrid offerings.

“Through powertrain diversification and new models, we will provide a broader range of options that cater to diverse customer preferences,” explains Nissan executive Guillaume Cartier. In other words, Nissan now sees hybrids as an essential part of its arsenal to woo buyers who aren’t ready to go fully electric. Other manufacturers are making similar U-turns.

”The industry should ’stop talking about [hybrids] as transitional technology’”

Ford and Honda put hybrids at the heart of long-term strategy

Ford’s chief, Jim Farley, recently argued that the industry should “stop talking about [hybrids] as transitional technology.” He noted that many Ford hybrids are already more profitable than their ICE-only counterparts. Honda, too, has rebalanced its strategy. It trimmed over $20 billion from its EV investment plans and is refocusing on hybrids in the late 2020s, after observing that American drivers still want larger vehicles with long range.

In a briefing, Honda’s CEO Toshihiro Mibe called hybrids a crucial stepping stone and revealed plans to launch multiple new hybrid models and powertrains by 2027 to meet “solid” demand, especially in North America, which he views as the “main battleground” for the carmaker’s hybrid models.

Hybrids gain ground as tactical, practical, policy-friendly path to lower emissions

Several factors explain these strategic shifts. One is consumer economics; hybrids offer significantly better fuel economy than standard ICE cars without the high upfront cost of a pure EV or the anxieties over charging infrastructure. For price-sensitive buyers, a hybrid powertrain in a popular SUV can save fuel and money immediately, whereas a comparable EV might still carry a steep price premium.

Another factor is regulatory pressure. Tough emissions rules are looming in the United States and Canada, but charging networks and battery supply chains are not yet ready to support a sudden 100% EV transition. Regulators appear willing to accept hybrids as a bridge technology to cut emissions in the near term. Automakers like GM are taking the hint, quietly hedging their bets with a few plug-in hybrids to ensure they can hit fleet emissions targets without betting the company on EVs alone.

How hybrids help carmakers hedge EV risks and preserve profits

Indeed, an industry study found that at least 15 major car brands, from Ford and General Motors to Audi and Toyota, have recently delayed some EV projects or shifted investment back towards hybrids and efficient ICE models.

There is also a pecuniary motive for car manufacturers and their retailers. Hybrids keep alive revenue streams that EVs threaten to shrink. Traditional automakers and dealerships have long relied on servicing and parts replacement (oil changes, brake pads, engine tune-ups) as a source of profit.

“With battery electric vehicles, [vehicle manufacturers] actually lose one of their key revenue streams”

A battery-electric car, with far fewer moving parts, upends that business model by drastically reducing maintenance needs. Hybrid vehicles, by contrast, still require regular servicing of their combustion engines and associated components. As a result, they can generate more post-sale revenue from maintenance than a pure EV.

“With battery electric vehicles, [vehicle manufacturers] actually lose one of their key revenue streams,” notes Andy Leyland of the consultancy SC Insights, whereas plug-in hybrids preserve much of that service income. In short, hybrids are not just an expedient for cautious consumers; they are attractive to carmakers as a way to keep the cash tills ringing during the slow march toward electrification.

Hybrids trade performance for practicality in battery-constrained times

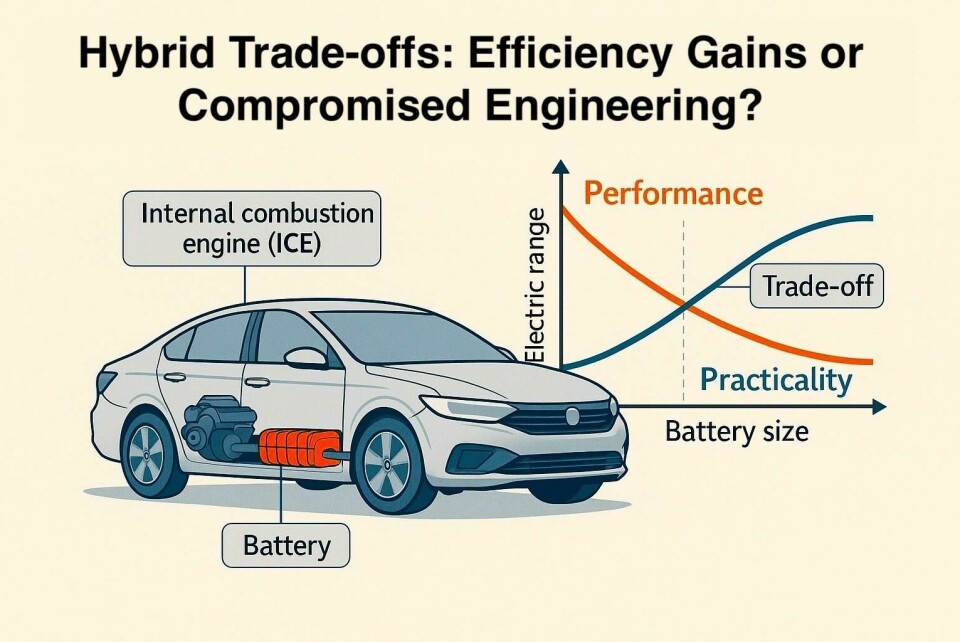

For all their appeal as a temporary solution, hybrids force designers and engineers into tricky compromises. One trade-off lies in battery sizing. A plug-in hybrid’s battery must be large enough to provide meaningful electric range, but small enough to keep cost and weight in check. The result is an apparent Goldilocks solution that in reality, satisfies no one completely.

Unlike a dedicated EV, which might carry a 75 kWh battery for hundreds of miles of range, a typical hybrid might tote a battery one-tenth that size. This limits a hybrid’s electric-only driving range to a few dozen miles at best.

Drivers still end up burning fuel on longer trips, and the vehicle carries the dead weight of an engine when running electric, and vice versa. Yet from a production standpoint, that smaller battery is a feature, not a bug. It uses far fewer critical minerals than a full EV’s pack.

Toyota has pointed out that the lithium and other raw materials needed for one long-range electric car could instead be used to build dozens of hybrid batteries. In fact, its engineers famously quantified that one EV’s battery could be repurposed into roughly 90 hybrids or 6 plug-in hybrids, delivering far greater total fuel savings across the fleet.

The implication is clear. Until battery supplies become abundant and cheap, spreading cells across many hybrids may achieve more aggregate benefit than putting all eggs in the all-electric basket.

”Automakers have responded by intensifying standardisation, sharing components across hybrid and non-hybrid models to keep costs down, and developing modular platforms flexible enough to handle batteries, motors and engines on the same assembly line”

Shared platforms are cost-efficient but sacrifice vehicle efficiency and performance

Another compromise is in platform engineering. Automakers crave the cost savings of building different powertrains on shared architectures, but a jack-of-all-trades platform inevitably involves sacrifices. Many carmakers have attempted to use one vehicle platform for ICE, hybrid and electric variants.

The approach saves money by reusing factories and parts, but it means the platform is never optimised for any one system. Engineers must leave room for either an ICE engine or a stack of batteries.

The chassis needs mounting points for an ICE powertrain as well as provisions for electric drive, an approach that inevitably adds mass and complexity. The extra structural bulk has earned such platforms the unflattering moniker of scar tissue. Vehicles built this way tend to be heavier or less space-efficient than those designed exclusively around one power source. By contrast, a pure EV platform can use the freed-up space (from the missing engine and gearbox) to add battery capacity or cabin room.

A dedicated ICE model faces none of the electric packaging constraints. Hybrids land somewhere in the middle, often carrying vestiges of both. For example, the removal of a fuel tank in an EV might allow a flat floor or extra storage, but a hybrid still needs that tank, robbing some of the design advantages of electrification.

Read more Hybrid stories

- Honda North America’s big investment in flexible manufacturing for EVs, hybrid and ICE vehicles

- Hybrid powertrains will continue to support the transition to vehicle electrification

- Digital twins drive powertrain transformation at HORSE Valladolid

- Hybrid powertrains – building the bridge to e-mobility

Hybrids add complexity but boost value in automotive manufacturing

Then there is the sheer parts content of a hybrid. An electric car famously has far fewer moving parts than a combustion one (no pistons, no complex transmission, no exhaust), which simplifies assembly. A hybrid, however, contains nearly everything an ICE vehicle has, plus the electric bits. Little surprise that industry analysis by Boston Consulting Group found hybrid-electric models have higher manufacturing value-added per vehicle than either pure ICE or pure EV models.

The hybrid’s dual drivetrain means extra subsystems (like regenerative braking hardware and two cooling circuits) and more manufacturing steps. Each additional component is another potential point of failure, both in production and in service. This complexity requires automotive engineers to balance two sets of trade-offs simultaneously. It is a testament to modern manufacturing techniques that hybrids can be built reliably at all, let alone at a competitive cost.

”Toyota’s long game reflects a view that hybrids are not merely a stopgap but a core part of reducing emissions for the next decade or more”

Honda flexes its flexible production muscles at Ohio

Automakers have responded by intensifying standardisation, sharing components across hybrid and non-hybrid models to keep costs down, and developing modular platforms flexible enough to handle batteries, motors and engines on the same assembly line.

Honda, for instance, is upgrading its Ohio factories with flexible production lines capable of handling ICE, hybrid and electric vehicles as demand dictates. This flexibility is expensive to implement, but it offers insurance against uncertainty. Manufacturers can dial hybrid output up or down in response to market demand without retooling entire plants.

Toyota doubles down on hybrids as rivals scale back electrics

No discussion of hybrids would be complete without Toyota, the carmaker that put the concept on the map. More than 25 years after the Prius first hit showroom floors, Toyota remains the world’s hybrid champion.

It has sold over 20 million hybrid cars globally and has kept faith in the technology even during the recent EV gold rush. That stance attracted criticism (some accused Toyota of dragging its feet on full electrics), but today it looks prescient.

While rivals retrench, Toyota’s hybrid lineup hums along profitably. In the United States, Toyota dominates hybrid sales in America - a leaked dealer briefing boasted that hybrids still outsold pure EVs by two to one among car shoppers - and that was in 2023. Toyota’s own models, of course, account for a large chunk of that volume.

The carmaker has steadily improved its hybrid systems, cutting costs and boosting performance, and it is now leveraging that expertise by even supplying hybrid batteries to competitors (starting in April 2025, Toyota began producing batteries for the roughly 400,000 Honda hybrids sold in the US).

Toyota’s long game reflects a view that hybrids are not merely a stopgap but a core part of reducing emissions for the next decade or more. “Self-charging” hybrids, as Toyota marketing likes to dub them, are pitched as practical and reliable, a contrast to some start-stop EV experiments by competitors. Toyota’s strategy of incrementalism, (that is; Kaizen), perfecting hybrids while gradually ramping up EV efforts is something of an outlier among big carmakers, but at the moment it appears to be paying off.

”BYD is also the world’s top manufacturer of plug-in hybrids”

China’s BYD makes the case for hybrids at massive scale

In China, a very different automaker offers another perspective on hybridisation. BYD, based in Shenzhen, has gained fame as one of the world’s largest EV producers, often seen as China’s answer to Tesla. Yet BYD is also the world’s top manufacturer of plug-in hybrids. This is evidence that even in an EV-forward market, hybrids have found a massive audience. BYD stopped making pure combustion cars in 2022 and now sells only “new energy” vehicles, which include both battery EVs and plug-ins. Last year it sold an astonishing 2.49 million passenger plug-in hybrids, a 73% jump from the year before.

Those hybrids made up more than half of BYD’s total sales, outnumbering its pure EV deliveries. Models like the BYD Qin and Song (ICE-EV hybrids with substantial electric range) are ubiquitous on Chinese roads. They thrive partly because Chinese consumers appreciate their flexibility, the underlying infrastructure, (no worries about finding a charger), and partly due to policy, as hybrids qualify for the same tax breaks and license plate perks as full EVs in many cities.

BYD’s success shows that hybrid technology can be scaled to extraordinary volumes if the market conditions are right. It also puts pressure on Western automakers; if an OEM widely celebrated for cutting-edge EVs still relies on hybrids for the majority of its volume, perhaps the dichotomy of EV versus hybrid is a false one.

In practice, the two technologies are complementary, serving different price points and use cases. Carmakers in North America have taken note; many are now eyeing the Chinese market’s path, where plug-in hybrids are a popular Plan B alongside pure electrics.

Hybrids accelerate automation and smart factories

The shift toward more electrified vehicles, hybrid or otherwise, is reshaping automotive factories and workforces. To build hybrids efficiently and at scale, manufacturers are leaning heavily on advanced automation and digital tools. Smart factories outfitted with thousands of sensors feed data into analytics systems, allowing real-time monitoring of production lines.

This data deluge enables predictive maintenance, identifying equipment wear or potential malfunctions before they cause costly downtime. At BMW’s Regensburg plant, for example, an AI-driven monitoring system now keeps watch over the assembly line’s conveyor equipment. It flags anomalies in power draw or component movement and has prevented an estimated 500 minutes of assembly disruption per year by catching faults early.

Across the industry, similar systems are being deployed to ensure that the added complexity of hybrid production does not translate into lower reliability or efficiency. Automakers have discovered that investments in preventative maintenance and Industry 4.0 technology pay for themselves by keeping those intricate production lines humming. As factories get smarter, the profile of the automotive workforce is changing. The assembly line of the hybrid era has more robots and fewer humans performing simple repetitive tasks.

Worldwide, the auto industry already employs over one million industrial robots (more than any other sector) and that number is set to grow. Robots excel at the precision and consistency needed to thread together dual drivetrain components.

Hybrid boom buys time as factories upskill for the electric era

Meanwhile, the demand for skilled technicians and engineers is rising. These are the people who program and maintain the robots, manage the battery assembly systems, and analyse the torrents of data coming from connected machines. In many plants the hiring mix is quietly shifting: fewer line workers, more maintenance technicians and software specialists. Building an electrified fleet calls for new expertise in high-voltage systems and electronics, so automakers are retraining many of their staff accordingly.

Some vehicle manufacturers, such as Ford and Volkswagen, report that it takes 30% less direct labour to assemble an EV than an ICE car. Hybrids, having both systems, have so far kept labour needs nearer to traditional levels, but this is likely a temporary state. As the balance later tilts more to pure EVs, analysts expect overall factory headcount to decline. The current hybrid boom may even be providing a useful buffer period: automakers can gradually redeploy workers and avoid abrupt layoffs, using the time to upskill employees for the fully-electric future.

”The carmakers that once spurned hybrids are now busy integrating them, all while touting grand EV ambitions for the 2030s”

One thing is certain. The North American auto industry’s journey to electrification will be an evolution, not a light-switch moment. Hybrid vehicles have re-emerged not as a technological dead-end, but as a critical stepping stone that is influencing factory investments and workforce planning.

The carmakers that once spurned hybrids are now busy integrating them, all while touting grand EV ambitions for the 2030s. It is a delicate balancing act: they must master the complexities of hybrid production and profit from it, without losing sight of the longer-term goal of fully electric line-ups. For the engineers on the shop floor, that means double the challenge today, in exchange for (hopefully) fewer headaches tomorrow.

And for now; and for the forseeable future, the hybrid car is enjoying a second life, acting as a catalyst of change inside the very plants that build the cars of the future.