The human side of artificial intelligence

The robots are coming, and we should all be welcoming them, according to BMW, which has a plan to introduce AI to its factories, starting from grassroots initiatives. Report by Illya Verpraet

Artificial intelligence or AI is one of those buzzwords that will soon either save or destroy the world, but it’s not always clear exactly how, not least for production workers on the floor of an automotive assembly plant. BMW is introducing AI into its production processes to boost efficiency and quality, but wants the initiative for new applications to come from the shop floor personnel, rather than be imposed from above.

Matthias Schindler, cluster supervisor for smart data analytics in the production system at BMW, explains that one of BMW’s goals is to democratise AI by making its applications open-source, and by getting the production staff on board: “Everybody should understand what AI is good for, what AI can do, what needs to be invested into AI to get it running 100% robustly,” he says. “And of course, we don’t want anybody to fear AI because this is some sort of monster. We also don’t want anybody to overestimate it because this isn’t a black box with a magician in it – you also have to invest something into the AI.”

DIY AI

To that end, BMW set up an internal communication campaign explaining advantages and requirements of AI and urging employees to come up with ideas about how AI could improve the production process or their own daily lives on the job. Schindler says that all the AI applications in use at the moment were developed based on requests from employees.

At the moment, AI is mainly proving its worth in the area of quality control, through object recognition. The prime example of this is an application that recognises whether the correct model designation badge such as 330i, 530e, X5, etc. has been placed on the right car.

Schindler recounts that an employee came to them, bored of his task to note the badge installed on the car and cross-checking it on the computer: “he would like to use this time for better, more interesting, more creative tasks, but as there was a car passing every 90 seconds in that case, there was no space left for more interesting tasks for him. With the help of AI, we can automate these tasks, and right now the employee has time to help his colleagues in process improvement and really added-value tasks.”

The popularity of the call to suggest use cases for AI prompted the team to develop a self-service application that can run on any computer and doesn’t require any coding, while the base code for the neural networks is freely available on software hosting platform GitHub.

BMW’s philosophy, according to Schindler, is that technology should serve people and that AI is just one more tool in the toolbox of the shop floor workers, who should understand what’s in it for them and how AI can improve their daily business.

“We have 50,000 production employees, so we cannot go through every single one of them and promptly solve their daily problems with a data scientist. This is why we bring them the self-service for AI, because we think that today’s algorithms are really powerful and they can be used by everybody.”

Despite the self-service possibilities, it is vital that AI applications that are introduced into a live system are 100% robust. They are developed at one location, brought to maturity and then rolled out to the production network. For instance, the badge recognition originated in Dingolfing and is now in the rollout phase for every plant.

“Everybody should understand what AI is good for, what AI can do, what needs to be invested into AI to get it running 100% robustly”

Open-source neural networks

It’s not just its own employees that are invited to use BMW’s AI developments, either. As the base code is published on GitHub, anyone can take it and build on it. Rather than giving away trade secrets, BMW sees it as democratising AI and opening the door to new partnerships.

Schindler explains: “[This way,] we have a very large user group testing our algorithms, which is really crucial for us because we have a very small [internal] team developing our algorithms. Having worldwide feedback really helps us to accelerate the entire development process.”

It also gives BMW access to world-class private developers, as well as software development companies, who would not ordinarily be interested in what an OEM is doing in manufacturing.

BMW’s AI developers didn’t start completely from scratch themselves, either. AI is always powered by an artificial neural network and many ready-made, pre-trained ones are freely available. BMW’s engineers test a number of them to find a suitable candidate for a particular use case, then the network has to be trained for the specific application using a set of training data.

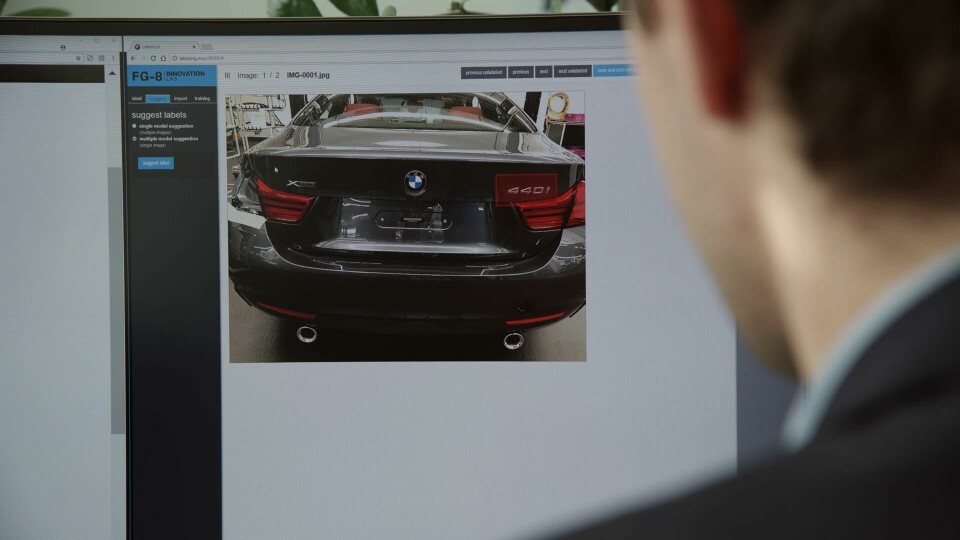

For the application where the AI verifies whether cars have been fitted with the correct model designations, that data set needs to contain around 100 to 1000 images per feature, which then has to be manually labelled so that the AI can match what it sees to the correct ‘answer’. Ultimately the complexity of what the AI needs to recognise informs how much data is required.

The size of the data set, which can get out control for some applications, is still one of the factors limiting the scope for AI. Schindler gives the example that “our colleagues always ask us: ‘is there any AI which would find any small scratch or dent anywhere on the vehicle’s outer skin?’. And this is still a limitation because on the one hand, we would have to have a very large data set. On the other hand, it would demand a very precise sensor when it comes to camera.”

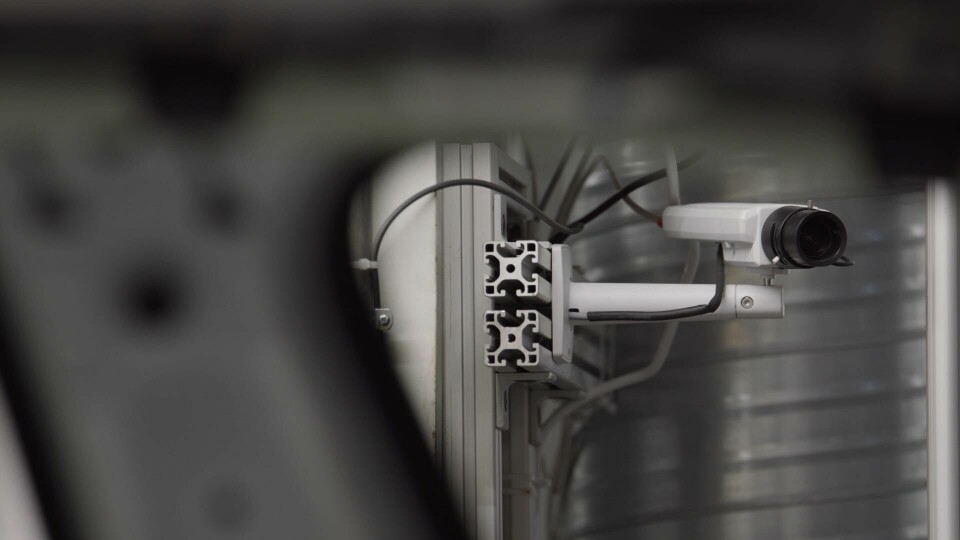

Although for some applications, the camera equipment is still a limiting factor, in a lot of cases the opposite is true. Schindler explains: “When you compare AI with conventional computer vision, the hardware – for example, the photo sensor, or the camera – can be much cheaper because AI is pretty robust when it comes to environmental conditions.

“To give you an idea, in the past, we had several cameras in what we call a camera booth, where one camera was responsible for one feature, which means that if you have a one-megapixel image, you would have 1 million pixels of one feature. It also means that if you want to check five features, you would have to buy five cameras.”

AI, on the other hand, can deal with lower resolutions and needs just one photo of the whole rear of the car – and therefore just one camera – to verify all the badges. Of course, the camera needs to be of industrial quality, and AI can place some higher demands on the computing hardware to ensure whatever the AI needs to do happens within the production line’s cycle time.

Schindler says AI is always cheaper on the software side, though, and requires less manual input: “We only take pictures, roundabout 100 pictures per feature. Afterwards, we label them. For example, we pull these rectangular bounding boxes around the respective area in every picture using our own BMW labelling tool, but that is it – no manual code writing or a definition of a grey scale.”

Ultimately, the goal of AI is not to replace people, Schindler says. Instead, it’s there to replace outdated, yet expensive technology, like computer vision booths, which require a lot of man hours and money to programme every single pixel, define the grey scale, check it and tighten the window of tolerance. Integrating AI-powered quality control into the production line also allows BMW to do away with dedicate camera booths, which take up space, but don’t contribute to production.

Rather than replace them, the AI should boost employees’ job satisfaction and give them the freedom to improve the products and processes. Schindler says: “We believe in our employees, who are the only ones that can see the car through the eyes of a customer. We want them to bring the finesse to a car, not perform repetitive or physically demanding tasks which robots or AI could perform just as well or even better. We want to have the optimal division of labour.”